“Hochelaga stands in the bright light of history for only one day.”

– Bruce Trigger, McGill anthropologist, in Cartier’s Hochelaga and the Dawson Site

“The mystery of what happened to these people has puzzled historians, archaeologists, linguists, and anthropologists for generations.”

– Darren Bonaparte, Mohawk historian, in Kaniatarowanenneh River of the Iroquois: The Aboriginal History of the St. Lawrence River

Long before the founding of McGill or the confederation of Canada, Indigenous peoples resided in the territories on which the university has been constructed. The most famous documentation of Indigenous life on these lands was written in 1535 by French explorer Jacques Cartier, who initiated the colonial project of New France at the behest of King Francis I. On his first voyage in 1534, Cartier kidnapped Dom Agaya and Taignoagny, sons of the chief of Stadacona, a St. Lawrence Iroquoian village located near present day Quebec City. After being ‘exhibited’ in France, Dom Agaya and Taignoagny told Cartier of a river that would lead him to the continent’s interior and the Iroquois settlement of Hochelaga. During his second voyage, Cartier took their guidance and became the first European to explore the St Lawrence River, a “discovery” regarded as his most significant.

After crossing the Atlantic for the second time, Cartier returned to Stadacona with Dom Agaya and Taignoagny. In his logbook, Cartier writes of their attempt to foil his journey to Hochelaga: “They dressed up three men as devils, arraying them in black and white dog-skins, with horns as long as one’s arm and their faces coloured black as coal, and unknown to us put them into a canoe.” According to Cartier’s account, Dom Agaya and Taignoagny warned that their god Cudouagny, as well as three apparent Christian deities had announced at Hochelaga that “there would be so much ice and snow that all would perish.” It seems likely that after a year in France, Dom Agaya and Taignoagny had started to recognize the nation’s imperialist agenda. It is possible that their warning was a ruse meant to deter Cartier from further exploration. Regardless, their predictions did indeed prove accurate that coming winter.

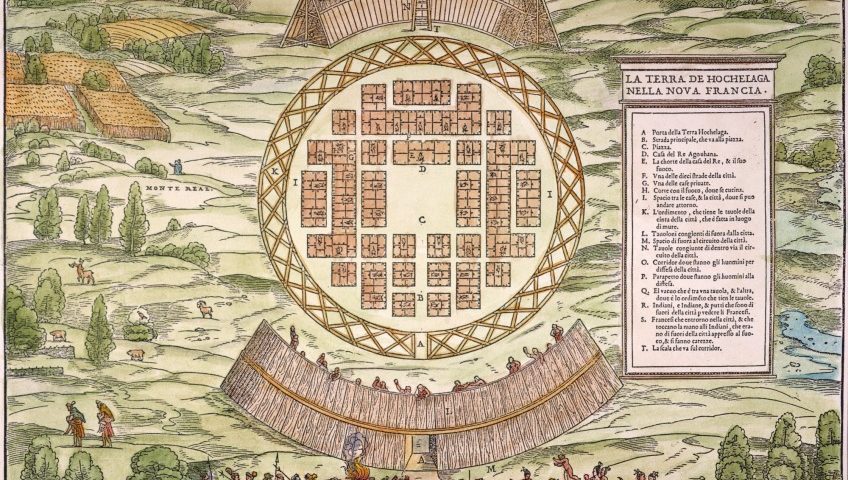

Before facing the harshness of winter however, Cartier explored the St. Lawrence river and arrived in Hochelaga on October 2, 1535. While the exact location of Hochelaga is unclear, Cartier writes of a village surrounded by expansive cornfields at the base of a large mountain (Mount Royal). As such, many suspect that Hochelaga was situated near where McGill currently stands. The fortified village was surrounded by three rows of palisades and contained at least fifty bark-covered longhouses – historians estimate that its population was around 1500 to 3000 residents. In other words, Hochelaga was not a small settlement but a major center and capital of sorts.

Cartier and his men were met by Hochelaga’s residents at a fire near the wood’s edge where they exchanged gifts, before proceeding to a welcome ceremony inside the village itself. This custom of twice meeting a distinguished guest resembles an Iroquois ceremony that is still celebrated today on the Six Nations reserve near Brantford, Ontario. During the welcome ceremony, Cartier was introduced to the chief of Hochelaga. Cartier gave Hochelaga’s inhabitants axes, knives, rings, and rosaries, while the Hochelagan Iroquois offered the Europeans fish, soup, beans, corn bread, and, during the ceremony, tobacco. Cartier’s logbook, likely written by a companion rather than Cartier himself, describes this encounter with Hochelaga’s inhabitants as such:

“During this interval, we came across on the way many of the people of the country, who brought us fish and other provisions, at the same time dancing and showing great joy at our coming. And in order to win and keep their friendship, the Captain [Cartier] made them a present of some knives, beads, and other small trifles, whereat they were greatly pleased. And on reaching Hochelaga, there came to meet us more than a thousand persons, men, women, and children, who gave us as good a welcome as ever father gave to his son, making great signs of joy…”

The following day, Cartier ascended the mountain, which he named Mount Royal in honour of his patron. Cartier realized the top of the mountain to be an ideal location for settlement, as its panoramic view provided a strategic advantage. The view from the top of Mount Royal also alerted Cartier to the Lachine Rapids and the impossibility of proceeding down the St. Lawrence. The following day, on October 4th, Cartier and his men began the journey back to Stadacona.

In line with Dom Agaya and Taignoagny’s warning, ice obstructed their access to the Atlantic forcing these Frenchmen to spend their first winter on Turtle Island. Donnacona, Chief of the Stadacona, helped Cartier and his crew overcome the threat of scurvy and starvation that winter. However, he was kidnapped by Cartier and died in France the following year.

Hochelaga was likely destroyed soon after Cartier’s visit. It is not mentioned in any account of Cartier’s return to the region in 1541 nor does Samuel de Champlain find the village when he attempts to seek it out in 1603. No other known account of Hochelaga exists and no material remains have been discovered.

Cartier’s visit to Hochelaga is critical to the establishment of settler colonialism in what is now called Canada. It is important to recognize that the widespread acknowledgement of Hochelaga’s existence is based on Cartier’s notes. Because his logbooks adhere to settler society’s methods of recording history and because he is a celebrated figure in Western history, Cartier’s account of Hochelaga is generally accepted to be reliable. Meanwhile, Indigenous histories not recorded by settlers are often dismissed as unverifiable. Furthermore, many early accounts of Hochelaga are adulterated by colonial fantasies.

For many centuries, many historians have sought look beyond nationalist mythology to uncover Hochelaga’s history and mysterious disappearance. Some of the main theories are that Hochelaga’s population was killed by diseases transmitted by Europeans, that they relocated to rebuild a new village surrounded by more fertile soil, or they were driven out by other Indigenous nations. With regard to the latter, the general consensus among historians is that European colonization up the St. Lawrence River through the 17th century gave rise to greater conflict between and among various Indigenous nations and rivalling European colonies for control of the lucrative fur trade. Evidence from the oral tradition suggests that Hochelaga was inhabited by St. Lawrence Iroquoians before the Haudenosaunee confederacy– formed in response to colonialism– became the primary occupant of the territory.